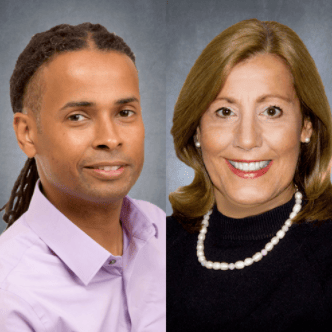

The second webinar in the “Eureka! Big Ideas for Big Changes in SPED” webinar series was with researcher Dr. Margo Izzo and disability advocate, author, poet, and consultant LeDerick Horne. During “New Insights for Building Disability Pride and Empowering Students with Hidden Disabilities,” Margo and LeDerick explained what hidden disabilities are, shared how educators can help destigmatize them, and shared ideas for helping connect students to positive role models, build on their assets, and advocate for the services they are guaranteed. After the webinar, our co-founder and co-CEO Clay Whitehead fielded audience questions for Margo and LeDerick. This lively discussion is provided below.

Clay: I’m interesting in the term disability pride. Why do you use that term? Disability pride. There’s a lot of other ways you could take that.

LeDerick: Well, in working on the book, Margo and I decided we wanted to have a distinct focus on identity and disability as being a positive identifier, very much as other groups promote pride, whether it be women’s pride, Asian pride, gay pride, or Black pride. We also wanted to make sure that at the center of our work we were including disability pride. We use disability as a general topic within the different groups, like the autism community or the deaf community. There are different disability groups who have promoted pride, but we were thinking about it in a very general way, again, just focusing in on the importance of identity.

Margo: When you think about pride, the opposite of pride is shame and experiencing stigma. Students who are coming to the classroom full of shame and feeling stigma and embarrassed have a greater challenge to learning. We know so many people with disabilities — visible and hidden — who have amazing gifts and talents. Think about Temple Grandin or Albert Einstein or Daymond John. They all accomplished a tremendous amount in their careers and it was in part their disabilities that gave them the insights to become a successful. So we call it disability pride as LeDerrick said to build on the pride movement, and if you don’t have disability pride and accept your disability you’re really at a disadvantage in both learning and career settings.

Clay: Right. I’ve used the term identifying in the special education context so much, but I so rarely think about the child’s identity as a source of leverage to empower them and help them know this is a part of them. This is something that we can really build on together. It’s so powerful, and it’s one of the most fundamental drivers that the two of you are accessing with what you are teaching.

Lets talk about that other use of identification. So how do you create a school culture that is more open to identifying children with hidden disabilities?

LeDerick: One of my mentors in special education in the disability world is a gentleman named Dr. William Henderson. He’s done a lot of work around inclusion practices. He was a school administrator at an elementary school up in Boston and retired recently. He wrote a really good book called “The Blind Advantage,” which details his life experiences a school administrator, and also a person with a visual impairment.He talks honestly about his life experiences and also about really pushing and wanting to create this ideal and inclusive school and all the realistic challenges that came with being able to make that happen. But his idea was to create a culture of inclusion, and inclusion is not just about having everybody in the same room together. Ideally it permeates the culture of the building so everybody learns about disability.

One of the things that I think is really key in being able to help identify students with disabilities is that we have to build everyone’s understanding and knowledge of disability, and that means everybody — all the students whether they are labeled or not. The teachers, the lunch lady, the bus drivers… everybody should have a sense of what disability is. When it comes to school culture, promoting culture, and what culture is, is that it’s art, it’s a ritual, it’s our behaviors, it’s our language. It’s being able to include disability as part of your school assemblies, your plays, covering people within your literature classes or your history classes. I think all that helps them build that culture of inclusion and that just makes it a lot easier for people to feel accepted if they do have a hidden disability.

Clay: LeDerick, that was a great reminder of how so many small interactions can have such an oversized impact in your day, your week, your month, or even in your development. I want to direct this next one to you, Margo. Let’s try to be specific if we can. How can we reframe disabilities, especially for students with multiple challenges, so we recognize their creativity and potential?

Margo: I really think we need to reframe disabilities at two levels: the system level and the student level. So, lets first look at the system. Our system was designed a lot by federal statute and we have this multi-factor evaluation process to identify the student’s deficits. Then we write goals in the student’s IEP to address those deficits and what we identify to be the specialized learning needs of that student.

That IEP process is almost exclusively focused on deficits and what the student can’t do, and I really think we need to take that IEP process and balance it with the student’s assets. Then we can help students identify their strengths and what they’re good at and use those strengths to enhance their ability to work on their goals. We did this in our college student learning communities for our STEM students with disabilities.

Here at Ohio State, we had a group of students with disabilities who really didn’t know their disability and didn’t know why they had an extended time on tests, or what the effects of their disability had on how they learned. We help them develop advocacy plans and that’s something that I think as a system we could help all students do.

So suggestions for administrators to reframe disabilities include encouraging teachers to conduct student led parent-teacher conferences for all students, not just students with disabilities. Students come to take ownership of their learning and begin to set goals. My daughter, before she was identified as a student with a disability, led a parent-teacher conference in the fourth grade and she was showing me her work samples, and then she presented some of her goals and what she wanted to work on, and it was a way for her to take ownership of her learning. I also think we need to empower teachers to learn about disabilities through professional development activities that address Positive Behavior Intervention Support and Response to Intervention so that they gain more knowledge on how to use these strategies to create a more positive learning environment for disability. And finally, it’s essential to build a culture within schools where there’s zero tolerance for bullying.

At the student level, we need to meet students individually to help them identify their strengths and interests, and we can use the path to disability pride to help students identify when they refuse support that might have enhanced their achievement and performance on a quiz or a test. And we can use that path to disability pride even in self-directed IEP materials. So helping students become more actively involved in the IEP has had a very positive result in students for getting on the path of disability pride.

For students with more intellectual disabilities or multiple disabilities, here at Ohio State we have a program with students with intellectual disabilities who are in college and preparing for employment. We have one student who had an intellectual disability, a significant speech impairment, and also a significant vision impairment and he was a good worker. He took direction well, he was cooperative, he was dependable, he did quality work, and when he had a question, he asked. He took the initiative to find out how to do something right. If our students could bring that attitude to their schoolwork as well as to their jobs, they will be able to be more successful and will have help in reframing disability at their own personal level.

Clay: LeDerrick, let me ask a question for you here. What programs and materials do you suggest to build knowledge, ownership, and self-esteem for students with learning disabilities?

LeDerick: This is a really interesting question, and something I hear quite a bit. I will just rattle off a few resources that I would recommend. Eye to Eye is a mentoring program whose board I’ve sat on for a number to years. We bring in college students who are labeled with learning disabilities and ADH,D but we recently have been promoting having chapters that are based in high schools so these young people would go to their local middle schools and mentor students. What it really does is build a safe place within the school so those with learning and attention issues can openly talk about what it means to be LD and again foster and support the development of disability pride.

In my own work and on social media, I share a lot of content that comes from understood.org and that’s a website that listed in our resource packet. Understood is quickly becoming a go-to place for a lot of resources for folks with learning and attention issues, and it’s targeting individuals themselves, as well as parents and school staff. I also had the pleasure of taking part in a really great documentary called “Being You,” which is a part of the Roadtrip Nation series. It documents the story of three young people with learning disabilities and attention issues as they get into an RV and cross the United States, and they meet a number of successful people with the same label. I think it just does a really good job of capturing some of the real life challenges and the real life fears, but it also shows them transforming and connecting to that community, which is one of the things we talk about and highlight as being so important as part of the path of disability pride.

So those are a number of the resources. Eye to Eye is also developing an app that will be available this fall. The app is designed to introduce people to the program but more than anything it helps them develop a presentation that they can bring into their IEP meeting so they can help develop a better understanding and knowledge of what their disability is and articulate it to people, like a member of their IEP team or their family.

Clay: Margo, what’s the best way to discuss emotional disabilities? We’ve talked about this a few times but how do you feel about discussing this about high school students? And any resources you could throw our way would be much appreciated. It’s a tough topic.

Margo: It is a tough topic. Students with emotional and behavior issues don’t have any understanding of the reason not to be achieving at school other than they’re emotional, their anxiety, or their depression. I taught high school students with emotional disturbance for three years and we had a lot of discussions about the choices they make and the natural consequences of those choices. If they wanted to get out of the special ed setting, what was it that the student needed to do to get back to their home high school? And what kind of choices do they want to make regarding careers? We spent a lot of time on correct exploration.

I even took my class to see a prison and discussed how their choices and actions will decide what kind of future they will have. I love the work that Dan Habib has done and the website Who Cares About Kelsey? which is highlighted in the resource packet. Dan actually follows a young woman with learning and behavior challenges and he did a documentary film. Kelsey was in a school that was using the PBIS framework. And so the website and the film provide a lot of applications of how to implement PBIS. It shows how the teachers were telling her, “I’m here for you, but I need to know where you want to go. We have rules, and you have to follow these rules or you’re sacrificing not only your own education but the education of your peers.”

So when you look at those websites like Who Cares About Kelsey? or thePBIS website that the US Department of Education has funded, you will find excellent resources and lots and lots of tips on how to connect with student with emotional disabilities.

Clay: You’re giving us lots to read and watch. I appreciate this. All too often it’s hard to find good video material and that’s something that can really bring this to life for a lot of us visual learners out there. So Margo, I bet you run into this problem. Hearing problems are often a hidden disability, but the hearing aid is not. How can we encourage the use of visible aids and accommodations when the student just wants to fit in?

Margo: Right. This is so critical at the high school level. I mean, the peer group is the most important audience that students have. Tamika Catchings has won four gold medals in the last four Olympics playing on the US women’s Olympic basketball team. As a child she threw her hearing aids away because she was teased at school. Then she refused to wear hearing aids for the rest of middle and high school. But she was a really good basketball player and she learned to accommodate her hearing loss by being really observant on the basketball court and watching people’s body language, and it helped her become one of the best women’s basketball players. She was MVP a couple of years in a row.

So helping our students, whether it’s hearing loss, an emotional disability, a learning disability, or ADHD involves helping them find those positive role models and they are out there for every disability. This is a way for them to connect with the positive attributes of other people with that same disability category and to help build that community.

When we were implementing EnvisionIT, we had the same issue with stigma and not wanting to use text-to-speech. So we used some universal design for learning principles and let every student use earbuds. We made it contingent that you could only listen to music if you were getting your work done. That way the students who needed to use text-to-speech didn’t feel the stigma because oftentimes in high school students aren’t at that point where they are willing to be so open about having a learning disability or hearing loss, or any kind of disability label.

Clay: LeDerrick, I’m going to come back to you here. How do we effectively combat teacher bias against students with hidden disabilities?

LeDerick: Unfortunately, in most of the programs that are in place to train teachers, it’s not mandatory that they receive a lot of training about what it means to support students with disabilities. Oftentimes those might be elective. So I think for school administrators, the onus is really on your shoulders to say that, “A lot of my teachers, although they are excellent, have not been trained to deal with students who have disabilities.” And that’s a real burden to place on those teachers, particularly as we push inclusion with all students. We want to make sure our teachers are prepared.

I think a big part of attacking that bias is by providing professional development experiences for our teachers around building disability awareness. It’s also helpful to have people who have disabilities, and especially young people who may have transitioned on into the adult world, come in and talk with your teachers about what their experiences were like.

I also think that there’s a lot of opportunity with being able to create spaces within our schools where teachers feel open to share with their colleagues that they have disabilities. Margo and I we spend a lot of time on stage. We shake a lot of people’s hands after we get done talking. A lot of times teachers take an opportunity to disclose to us, “Hey, I have a disability, too.” And some of them are open about that with their students. Some are open with some of their colleagues but sometimes they don’t feel really comfortable being able to talk about that.

You also have an opportunity during training sessions and meetings before the school year starts to to highlight a teacher who has had a positive experience of working with people with disabilities and really hold them up as an example. Give them an opportunity to maybe even mentor other teachers. And again, creating spaces where we can allow our teachers to openly talk about some of the challenges they had in school, whether they had a label or not, just helps them normalize what disability is.

Clay: How does race intersect with disability bias in disciplining young men or color?

LeDerick: This is a complicated topic. In my own experience as a student in special education and being in a self-contained special ed class for the first three or so years in special ed, the vast majority of the students that I was in classes with were all black and primarily black males. In both rural communities and urban settings, there tends to be some disproportionality in place in who ends up being labeled with a disability as well as the disproportionality related to discipline.

In some of the research that I’ve read around disproportionality, the experts often point to a need for cultural competence training much like we’ve talked about what it means to educate people about disabilities. There’s a lot of bias, a lot of prejudice, and people who may have really good hearts but did not have that professional background. So providing that sort of training is helpful.

Margo has that excellent colleague at Georgetown University, Tawara Goode, who actually provides cultural competency assessments to our schools and our organizations. So that is one resource I would point to in order to combat bias. There’s a need for more education around race and how that effects disciplinary practices. Having a really quality behavior support program in place in your school can also mitigate a lot of issues.

Clay: Thank you for that answer. Margo, we have time for one more question for you. What are some ways to help students accept their disability when preparing for the world of work?

Margo: That’s an excellent question and has been the focus of my career. I really want to engage in students and transition planning. When you’re planning for work, the toughest thing for high school students is developing a realistic and valid career goal. We have students that want to be an NBA basketball star or a football star because they make a lot of money, but then they really don’t have the speed or the weight or the agility to be successful on the court or the football field. So that is one of the reasons we developed the EnvisionIT curricula, and the federal government has now given us a contract to scale that up to schools all across the country.

We have a video of LeDerrick reading one of his poems in the EnvisionIT curriculum to motivate students to find their path and to be all that they can be. Students can do an age-appropriate transition assessment online. Our research indicates that students need to learn how to use the internet and learn the difference between a .com and a .org and a .edu so they can better evaluate whether or not they are getting accurate information on the web.It’s that process of career exploration and then looking at that job and looking at yourself. Your interest, you abilities, and determining whether there’s a match there. And if there isn’t a match then you keep looking for a career area where there is a match.

The one thing that I want to add is that our employment world still does have some disability issues. Unfortunately, there is a bias against hiring people with disabilities in some settings, and so we’ve encouraged some students not to disclose about their disability until they get a job offer, but when they accept the job offer they can disclose it and share what kinds of accommodations they believe they will need. The 411 on Disability Disclosure is an excellent resource that teachers can use to walk students through that process.